In 1519, Hernán Cortés and a small group of Spanish soldiers made first contact with the Aztecs. The stories they sent back to Europe detailing the wealth and sophistication of the Aztec empire astonished their countrymen – and fed 300 years of efforts to write and re-write the story of the Mexican Conquest.

From Oct. 1 through Jan. 23, 2011, the History Museum’s Triangle Gallery will present Imagining Mexico: From the Aztec Empire to Colonial New Spain, an original exhibit featuring books, prints and maps from the Fray Angélico Chávez History Library’s John Bourne Collection of Meso-Americana, the Rare Books Collection, and the Map Collection. Created mainly for people who would never cross the Atlantic but live their adventures vicariously, the works formed perceptions – fictitious at times – of the land of Cortés, Moctezuma, amazing temples and important battles.

An opening reception will be held from 5:30-7 pm on Friday, Oct. 1. The Museum of New Mexico Women’s Board will serve light refreshments in the museum lobby.

“Beginning shortly after the fall of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, the story of the Conquest of Mexico has been told and retold countless times, in both word and image,” said Khristaan D. Villela, scholar-in-residence at the museum and a curator of Imagining Mexico. “Each version built upon and elaborated those before, resulting in a range of imaginations of the Conquest and ancient Mexico that are reflections, and sometimes refractions.”

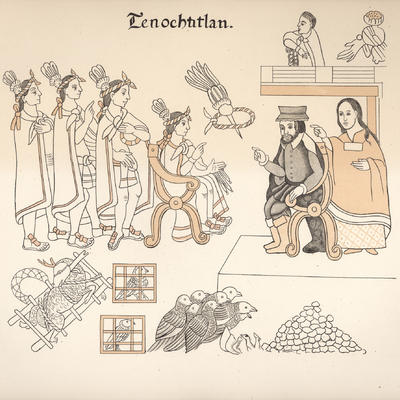

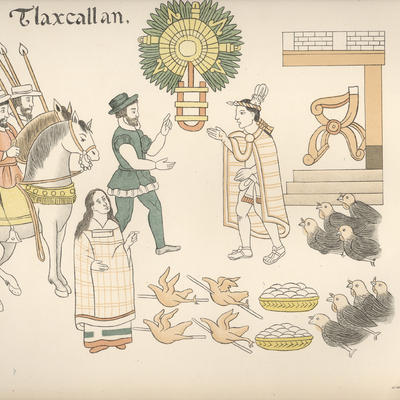

The players in the conquest and European colonization of Mexico had direct ties to what would later be called New Mexico. Juan de Oñate married a woman who was Cortés’ granddaughter and the great-granddaughter of Moctezuma II, the Aztec emperor. Cortés’ most steadfast allies, the Tlaxcalans, are reputed to have accompanied the first colonizers of New Mexico as mercenaries who settled near the San Miguel church in the Barrio of Analco. (In Nahuatl, Analco means “near the water.”)

New Mexico’s history parallels Mexico’s in its cycles of conquest and colonization. Descendents of both Native peoples and colonizers continue to inhabit both places in large numbers, and we do not agree on our history. The books, prints, and maps in this exhibition show that history is in flux, and that one generation’s image of the Aztecs was, in the next, deemed inaccurate and fanciful.

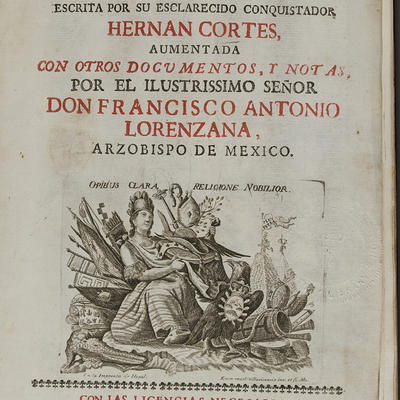

Among the items on display:

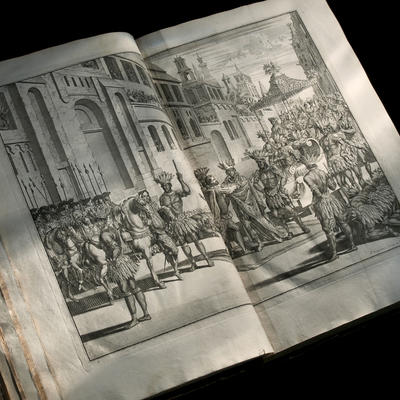

Images of the Aztec Templo Mayor. The main shrine in the capital of Tenochtitlan, the Templo Mayor’s size and appearance was forgotten soon after the last battles of the conquest in 1521. Some of the images show it with twin staircases and shrines; others imagine a vast platform with staircases around its base – a veritable Tower of Babel. The variance between the images epitomizes the range of interpretations about the conquest and Pre-Columbian Mexico.

Early maps of New Spain. A 1769 map by Antonio Alzate of Mexico was one of the earliest to use the names Texas and California (though it shows the latter as an island). An 1803 map by Alexander von Humboldt of Germany shows the route of El Camino Real from Mexico City to Santa Fe.

Four images from Lienzo de Tlaxcala. Originally painted on a large linen sheet in 1550, the Lienzo tells the story of the conquest from the point of view of the Tlaxcalans, native Mexicans whose alliance with Cortés was perhaps the deciding factor in his victory over Moctezuma II and the Aztec Empire. Besides the four images, the complete Lienzo de Tlaxcala Codex will be presented digitally in the exhibit.

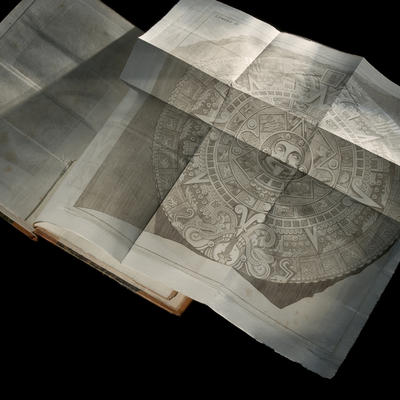

The first book about the Aztec Calendar Stone. Buried about 1550 by order of the Archbishop of Mexico, the stone was rediscovered in 1790 in Mexico City. A proposal to turn it into a cathedral step to symbolize the triumph of Christianity over the pagan Aztecs was rejected after authorities became convinced it was an astronomical and mathematical device worthy of preservation. It was, in fact, a sacrificial altar commissioned by Moctezuma II, and remains the best-known Native American artwork of the period.

The exhibit also presents the first engraving of the sculpture, made by a Mexican artist best-known for his images of the Virgin Mary and Catholic saints.

“These are amazing books with even more amazing prints and fold-out maps hidden between their covers showing Spain’s – and by extension Europe’s – understanding of the new world,” said Tomas Jaehn, director of the Chávez History Library.

Beyond their content, the books themselves stand as impressive artifacts.

"The books in this well-preserved collection, some in their original bindings and some beautifully re-bound, along with their fine marbled and handmade papers, are beautiful examples book-making history,” said Tom Leech, curator of the Palace Press.

Part of Imagining Mexico’s run coincides with another History Museum exhibit, Threads of Memory: Spain and the United States, featuring nearly 140 rare documents, maps, prints and paintings on loan from Spain from Oct. 17-Jan. 9, 2011. Taken together, the exhibits portray how European explorers and colonists interpreted what they found here.

The Triangle Gallery is on the mezzanine level of the museum, next to the Auditorium.

To download high-resolution images from this exhibit, click on "Go to Related Images" below.